Labor Day is a Reminder that ‘More Jobs’ Should Mean ‘Better Jobs’

On June 10, 1872, an estimated 150,000 workers marched through New York City to celebrate the end of a three-month, statewide strike. The purpose of the strike? The eight-hour workday. Across the country, similar victories soon followed. In the battle for an eight-hour workday, workers faced opposition at every step. Employers reduced wages to accommodate the decrease in workers’ hours. State lawmakers added loopholes to laws, like in Illinois where eight-hour days were enforced unless there was a “special contract to the contrary.” Employers in the state then stipulated that only workers who signed contracts to work longer hours could keep their jobs. But the workers persisted.

The labor movement in the United States was born from the simple fact that not all jobs in the US were good jobs. While the situation for workers has improved substantially since the 1800s, some issues continue almost 150 years later. Workers still march in cities across the country for a living wage. And much like the fight for the eight-hour day, workers face opposition at practically every step, especially at the federal level.

The Trump Administration is quick to point out any gains in the monthly jobs numbers, but absent from that conversation is whether we are seeing an increase in “good” jobs. A good job, in this case, is defined as one with growing wages and strong worker protections. Based on those criteria, the sad truth is not all jobs in the US are good jobs.

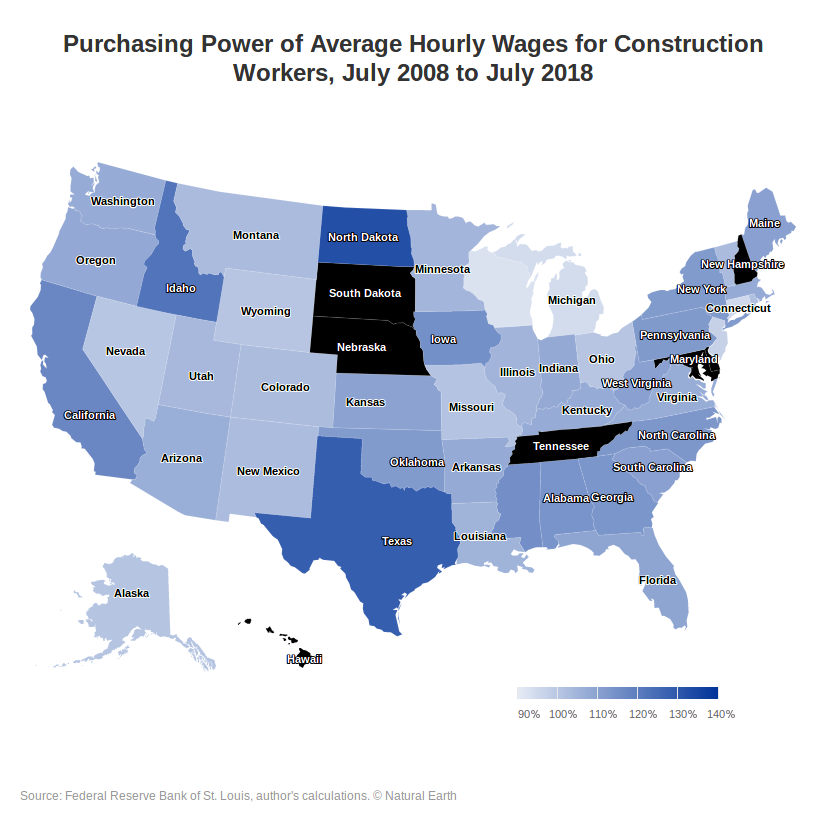

While wages have been growing, not all wages have kept up with inflation. In Idaho, the average hourly earnings for manufacturing workers in July of 2018 was 88 percent of what they earned in July of 2008, in terms of purchasing power. For manufacturing and construction workers in Michigan, the average hourly earnings were 92 percent and 94 percent, respectively, of what they earned in July of 2008. Construction workers in Wisconsin, Connecticut, and New Jersey have average hourly earnings that are 93 percent, 95 percent, and 97 percent of what they earned a decade ago, in terms of purchasing power.

Construction firms, however, are claiming that they are having difficulty finding qualified workers, according to a recent survey by the Associated General Contractors of America. In Michigan, where real wages have decreased since 2008, 77 percent of 32 respondents say they are having a hard time filling some or all hourly craft positions. But only 38 percent of respondents say they have increased base pay for hourly workers in the past year, and 3 percent increased benefit contributions and/or improved employee benefits. Only 14 percent of those who haven’t increased pay are considering it, and 17 percent are not considering increases in pay or benefits. The responses from firms in Wisconsin, where real wages have also decreased, are similar. Even in states, where real wages have grown since the recession, yearly growth can be measured in tenths of one percent. As CEPR has pointed out many, many times, if there is a shortage of construction workers, why aren’t more employers raising pay?

When it comes to weak worker protection, West Virginia and Missouri stand out in particular. West Virginia is a “right to work” state, meaning the state prohibits requirements for employees to join a union or pay “fair share” fees to be included in a bargaining unit. Republican lawmakers tout “right to work” and other policies as driving the state’s economic growth. However, according to a recent report by Janelle Jones and Heidi Shierholz at the Economic Policy Institute, “right to work” laws do not actually boost jobs. They merely succeed in weakening the collective bargaining power of unions and lowering wages and reducing benefits for both union and nonunion workers. Between 2016 and 2017, the percentage of workers represented by a union in West Virginia declined, from 13.2 percent to 11.9 percent. And while overall employment has grown by 0.9 percent in West Virginia in the last year, as Ted Boettner of the West Virginia Center on Budget and Policy and CEPR senior economist Dean Baker point out, the state has 9,000 fewer jobs since the beginning of the Great Recession. The number of construction jobs in the state remains around the same as at the end of the recession, and in manufacturing, the six-month moving median in month-to-month job growth as a percentage change was -0.32 percent. Manufacturing workers’ average hourly earnings in July 2018 were 99 percent of what they earned a decade ago, in terms of purchasing power.

Missouri has also been a hostile state for unions. Between 2016 and 2017, the percent of members of unions employed in the state declined, from 9.7 percent to 8.7 percent. Missouri is not a “right to work” state, but not for the lack of trying by state politicians. Last year the state general assembly passed a “right to work” law, but in August voters blocked the law via a referendum, with 67 percent of voters rejecting the proposition. Other anti-union laws have been passed, however, such as HB 1413, which requires public sector workers to recertify their union every three years by a majority vote. In Missouri, growth in construction jobs has been stagnant since the recovery, and in manufacturing the six-month moving median in month-to-month job growth as a percentage change was -0.07 percent.

Like the voters in Missouri have recently shown, protecting workers’ jobs, wages and benefits is not a responsibility that should be left to the federal government, the states, or employers. Under their watch, the ability of workers to collectively bargain and make the workplace better for everyone has been eroding.

Shortly after workers celebrated the victory of the eight-hour day in the late 1800s, a movement grew in the US to recognize workers with an official public holiday called “Labor Day.” It became an official federal holiday in 1894. Now Labor Day is mostly known for the end of summer and back-to-school sales, but it should be a reminder that jobs should and can be good again.

Construction Eight-hour day Idaho Illinois Labor Day Living wage Manufacturing Michigan Missouri New Jersey New York Unions West Virginia Wisconsin